Like many languages, English has wide variation in pronunciation, both historically and from dialect to dialect. In general, however, the regional dialects of English share a largely similar (though not identical) phonological system.

Phonological analysis of English often concentrates on, or uses as a reference point, one or more of the prestige or standard accents, such as Received Pronunciation for England, General American for the United States, and General Australian for Australia. Nevertheless, there are very many dialects of English spoken and they do not necessarily descend from any of these standardised accents. These standardised accents function only as a limited guide for the knowledge of English phonology, which one can later expand upon once one becomes more familiar with some of the many other dialects of English that are spoken.

Phonemes

A phoneme of a language or dialect is an abstraction of a speech sound or of a group of different sounds which are all perceived to have the same function by speakers of that particular language or dialect. For example, the English word "through" consists of three phonemes: the initial "th" sound, the "r" sound, and an "oo" vowel sound. Notice that the phonemes in this and many other English words do not always correspond directly to the letters used to spell them (English orthography is not as strongly phonemic as that of certain other languages).

The phonemes of English and their number vary from dialect to dialect, and also depend on the interpretation of the individual researcher. The number of consonant phonemes is generally put at 24 (or slightly more). The number of vowels is subject to greater variation; in the system presented on this page there are 20 vowel phonemes in Received Pronunciation, 14â€"16 in General American and 20â€"21 in Australian English. The pronunciation keys used in dictionaries generally contain a slightly greater number of symbols than this, to take account of certain sounds used in foreign words and certain noticeable distinctions that may not beâ€"strictly speakingâ€"phonemic.

Consonants

The following table shows the 25 consonant phonemes found in most dialects of English. When consonants appear in pairs, fortis consonants (i.e. aspirated or voiceless) appear on the left and lenis consonants (i.e. lightly voiced or voiced) appear on the right:

- Most varieties of English have syllabic consonants in some words, principally [lÌ©], [mÌ©] and [nÌ©], for example at the end of bottle, rhythm and button. In such cases, no vowel is pronounced between the last two consonants. It is common for syllabic consonants to be transcribed with a subscript mark, so that phonetic transcription of bottle would be [ˈbÉ'tlÌ©] and for button [ˈbÊŒtnÌ©]. In theory, such consonants could be analysed as individual phonemes. However, this would add several extra consonant phonemes to the inventory for English, and phonologists prefer to identify syllabic nasals and liquids phonemically as /É™C/. Thus button is phonemically /ˈbÊŒtÉ™n/ and 'bottle' is phonemically /ˈbÉ'tÉ™l/.

- The voiceless velar fricative /x/ is mainly restricted to Scottish English; words with /x/ in Scottish accents tend to be pronounced with /k/ in other dialects. The velar fricative may appear in recently borrowed words such as chutzpah. Hiberno-English usually maintains /x/, also.

- The sound at the beginning of words spelt ⟨wh⟩ (e.g. which, why) is in some accents (e.g. much of the American South, Scotland, and Ireland) a "voiceless w" sound, which is a voiceless labiovelar fricative or voiceless labiovelar approximant, whereas other accents have the voiced approximant [w]. The phonemic status of the voiceless sound, for which the phonetic symbol is [Ê], is difficult to define. It would be possible to consider this sound to be a separate phoneme, but phonologists prefer to treat it as a combination of /h/ and /w/. Thus which (as pronounced by speakers who have the "voiceless w") is transcribed phonemically as /hwɪtʃ/. This should not, however, be interpreted to mean that such speakers actually pronounce [h] followed by [w]: the phonemic transcription /hw/ is simply a convenient way of representing a single sound [Ê] without analyzing such dialects as having an extra phoneme.

- A similar case to the above is that of the sound at the beginning of huge in dialects such as British English; in accents in which the initial consonant is voiceless, a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] occurs, but the usual phonemic analysis is to treat this as /h/ plus /j/ so that huge is transcribed /hjuËdÊ'/. This transcription often gives rise to the incorrect belief that speakers pronounce [h] followed by [j] in such contexts, but the symbols in fact represent a single sound [ç]. The yod-dropping found in Norfolk dialect means that the traditional Norfolk pronunciation of huge is [hÊŠudÊ'] and not [çuËdÊ'].

- Rhoticity, the phonotactic constraints regarding the phoneme /r/, differ among accents. In non-rhotic accents, such as Received Pronunciation and Australian English, /r/ only appears before a vowel, whereas in rhotic accents /r/ occurs in all positions.

The following table shows typical examples of the occurrence of the above consonant phonemes in words.

The distinctions between the nasals are neutralized in some environments. For example, before a final /p/, /t/ or /k/ there is nearly always (with "dreamt" being a notable exception) only one nasal sound that can appear in each case: [m], [n] or [Å‹] respectively (as in the words limp, lint, link â€" note that the n of link is pronounced [Å‹]). This effect can even occur across syllable or word boundaries, particularly in stressed syllables: synchrony is pronounced [ˈsɪŋkɹəni] whereas synchronic may be pronounced either as [sɪŋˈkɹÉ'nɨk] or as [sɪnˈkɹÉ'nɨk]. For other possible syllable-final combinations, see Coda in the Phonotactics section below.

Allophones of consonants

Although regional variation is very great across English dialects, certain instances of allophony can be observed in all (or at least the vast majority) of English accents. (See also Allophones of vowels below.)

- Many dialects have two allophones of /l/ â€" the "clear" L and the "dark" or velarized L. The clear variant is used before vowels when they are in the same syllable, and the dark variant when the /l/ precedes a consonant or is in syllable-final position before silence. In some dialects, /l/ may be always clear (e.g. Wales, Ireland, the Caribbean) or always dark (e.g. Scotland, most of North America, Australia, New Zealand).

- Depending on dialect, /r/ has at least the following allophones in varieties of English around the world:

- alveolar approximant [ɹ]

- postalveolar or retroflex approximant [É»]

- labiodental approximant [Ê‹]

- alveolar flap [ɾ]

- postalveolar flap [ɽ̺]

- alveolar trill [r]

- In the traditional Tyneside accent in the North of England, /r/ was pronounced as a voiced uvular fricative [Ê], but this is probably now extinct.

- In some rhotic accents, such as General American, /r/ when not followed by a vowel is realized as an r-coloring of the preceding vowel or its coda.

- For many speakers, /r/ is somewhat labialized, as in reed [ɹʷiËd] and tree [tʰɹ̥ʷiË]. In the latter case, the [t] may be slightly labialized as well.

- Postalveolar consonants are also usually labialized (e.g. /ʃ/ is pronounced [ʃʷ] and /Ê'/ is pronounced [Ê'Ê·]).

- The voiceless stops /p/, /t/ and /k/ are aspirated ([pÊ°], [tÊ°], [kÊ°]) at the beginnings of words (for example tomato) and at the beginnings of word-internal stressed syllables (for example potato). They are unaspirated ([p], [t], [k]) after /s/ (stan, span, scan) and at the ends of syllables.

- In American English, both /t/ and /d/ can be pronounced as a voiced flap [ɾ] in certain positions: when they come between a preceding stressed vowel (possibly with intervening /r/) and precede an unstressed vowel or syllabic /l/. Examples include water, bottle, petal, peddle (the last two words sound alike). The flap may even appear at word boundaries, as in put it on. When the combination /nt/ appears in such positions, some American speakers pronounce it as a nasalized flap that may become indistinguishable from /n/, so winter may be pronounced similarly or identically to winner.

- In many accents of English, voiceless stops (/p/, /t/, /k/ and /tʃ/ are glottalized. This may be heard either as a glottal stop preceding the oral closure ("pre-glottalization" or "glottal reinforcement") or as a substitution of the glottal stop [Ê"] for the oral stop (glottal replacement). /tʃ/ can only be pre-glottalized. Pre-glottalization normally occurs in British and American English when the voiceless consonant phoneme is followed by another consonant or when the consonant is in final position. Thus football and catching are often pronounced [ˈfÊŠÊ"tbÉ"ËÉ«] and [ˈkʰæÊ"tʃɪŋ], respectively. Glottal replacement often happens in cases such as those just given, so that football is frequently pronounced [ˈfÊŠÊ"bÉ"ËÉ«]. In addition, however, glottal replacement is increasingly common in British English when /t/ occurs between vowels if the preceding vowel is stressed; thus getting better is often pronounced by younger speakers as [ˈɡeÊ"ɪŋ ËŒbeÊ"É™].

- Final /t/ as in cat is not usually audibly released. However, in speech with careful enunciation, in all situations /t/ may be pronounced [t] or [tÊ°].

The foregoing features mean that English voiceless plosive consonants have a wide range of different allophones.(p: 62â€"67)

Vowels

The vowels of English differ considerably between dialects. Because of this, corresponding vowels may be transcribed with various symbols depending on the dialect under consideration. When considering English as a whole, lexical sets are often used, each named by a word containing the vowel or vowels in question. For example, the LOT set consists of words which, like lot, have /É'/ in Received Pronunciation and /É'/ in General American. The "LOT vowel" then refers to the vowel that appears in those words in whichever dialect is being considered, or (at a greater level of abstraction) to a diaphoneme which transcends all dialects. A commonly used system of lexical sets is presented below; for each set, the corresponding phonemes are given for RP (first column) and General American (second column), using the notation that will be used on this page.

For a table that shows the pronunciations of these vowels in a wider range of English dialects, see IPA chart for English dialects.

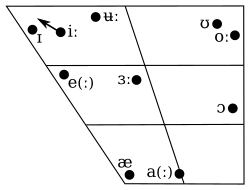

The following tables show the vowel phonemes of three standard varieties of English. The notation system used here for Received Pronunciation (RP) is fairly standard; the others less so. For different ways of transcribing General American, see Transcription variants below. The feature descriptions given here (front, close, etc.) are abstracted somewhat; the actual pronunciations of these vowels are more accurately conveyed by the IPA symbols used (see Vowel for a chart indicating the meanings of these symbols; though note also the points listed below the following tables).

The differences between these tables can be explained as follows:

- RP uses /e/ rather than /É›/ largely for convenience and historical tradition; it does not necessarily represent a different sound from the General American phoneme.

- In General American, the vowels [ə], [ʌ] and [ɜ] may be considered a single phoneme.

- General American lacks a phoneme corresponding to RP /É'/ (LOT, CLOTH), instead using /É'/ or /É"/ in such words.

- In certain American English dialects, the diphthongs /ɪə/ and /eə/ can be found in words such as "ideas" and "rail," respectively.

- The different notations used for the vowel of GOAT in RP and General American (/əʊ/ and /oʊ/) reflect a difference in the most common phonetic realizations of that vowel.

- The different notations used here for some of the Australian vowels reflect the phonetic realization of those vowels in Australian: a central [ʉË] rather than [uË] in GOOSE, a more closed [e] rather than [É›] in DRESS, an open-mid [É"] rather than RP's [É'] in LOT and CLOTH, a more close [oË] rather than [É"Ë] in THOUGHT, NORTH and FORCE, a fronted [a] rather than [ÊŒ] in STRUT, a fronted [aË] rather than [É'Ë] in CALM and START, and somewhat different pronunciations of most of the diphthongs.

- The Australian monophthong /eË/ corresponds to the RP diphthong /eÉ™/ (SQUARE).

- Australian has the badâ€"lad split, with distinctive short and long variants of [æ] in various words of the TRAP set.

- The vowel /ÊŠÉ™/ is often omitted from descriptions of Australian, as for most speakers it has split into the long monophthong /oË/ (e.g. poor, sure) or the sequence /ʉË.É™/ (e.g. cure, lure).

Other points to be noted are these:

- Although the notation /ÊŒ/ is used for the vowel of STRUT in RP, the actual pronunciation is closer to a near-open central vowel [É]. The symbol ÊŒ continues to be used for reasons of tradition (it was historically a back vowel) and because it is still back in other varieties.

- A significant number of words (the BATH group) have /æ/ in General American, but /É'Ë/ in RP (and mostly /aË/ in Australian).

- Some speakers of some American English dialects do not distinguish /É'/ from /É"/ (see cotâ€"caught merger).

- In General American (which is a rhotic accent, where /r/ can still occur in positions where it does not precede a vowel), many of the vowels can be r-colored by way of realization of a following /r/. This is often transcribed phonetically using a vowel symbol with an added retroflexion diacritic [Ëž]; thus the symbol [Éš] has been created for an r-colored schwa (sometimes called "schwar") as in LETTER, and the vowel of START can be modified to make [É'Ëž] so that the word 'start' may be transcribed [stÉ'Ëžt]. Alternatively, the START vowel might be written [stÉ'Éšt] to indicate an r-colored offglide. The vowel /Éœ/ (as in NURSE) is generally always r-colored, and this can be written [É] (or as a syllabic [ɹ̩]).

- In RP and other dialects, many words from the CURE group are coming to be pronounced by an increasing number of speakers with the NORTH vowel (so sure is often pronounced like shore). Also the RP vowels /ɛə/ and /ÊŠÉ™/ may be monophthongized to [É›Ë] and [oË] respectively.

- Long vowels are often not pronounced as pure monophthongs. In particular, the vowels of FLEECE and GOOSE are usually pronounced as narrow diphthongs: [ɪi], [ʊu].

Allophones of vowels

Listed here are some of the significant cases of allophony of vowels found within standard English dialects (see also Allophones of consonants above).

- There is a tendency for many vowels to be pronounced with greater length in open syllables than closed syllables, and with greater length in syllables ending with a voiced consonant than with a voiceless one. For example, the /aɪ/ in advise is longer than that in advice.

- In many accents of English, tense vowels undergo breaking before /l/, resulting in pronunciations like [pʰiəɫ] for peel, [pʰuəɫ] for pool, [pʰeəɫ] for pail, and [pʰoəɫ] for pole.

- In RP, the vowel /əʊ/ may be pronounced more back, as [É'ÊŠ], before syllable-final /l/, as in goal. In Australian English the vowel /əʉ/ is similarly backed to [É"ÊŠ] before /l/.

- The vowel /aɪ/ may be pronounced less open before a voiceless consonant. Thus writer may be distinguished from rider even when flapping causes the /t/ and /d/ to be pronounced identically.

- The vowel /É™/ is often pronounced [É] in open syllables.

Unstressed syllables

Unstressed syllables in English may contain almost any vowel, but there are certain sounds â€" characterized by central position and weakness â€" that are particularly often found as the nuclei of syllables of this type. These include:

- schwa, [É™], as in COMMA and (in non-rhotic dialects) LETTER; also in many other positions such as about, photograph, paddock, etc. This sound is essentially restricted to unstressed syllables exclusively. In the approach presented here it is identified with the phoneme /É™/, although other analyses do not have a separate phoneme for schwa and regard it as a reduction or neutralization of other vowels in syllables with the lowest degree of stress.

- r-colored schwa, [ɚ], as in LETTER in General American and some other rhotic dialects, which can be identified with the underlying sequence /ər/.

- syllabic consonants: [l̩] as in bottle, [n̩] as in button, [m̩] as in rhythm. These may be phonemized either as a plain consonant or as a schwa followed by a consonant; for example button may be represented as /ˈbʌtn̩/ or /ˈbʌtən/.

- [ɪ], as in roses, making, expect. This can be identified with the phoneme /ɪ/, although in unstressed syllables it may be pronounced more centrally (in American tradition the barred i symbol /ɨ/ is used here), and for some speakers (particularly in Australian and New Zealand and some American English) it is merged with /ə/ in these syllables. Among speakers who retain the distinction there are many cases where free variation between /ɪ/ and /ə/ is found, as in the second syllable of typical. (The OED has recently adopted the symbol /ᵻ/ to indicate such cases.)

- [ʊ], as in argument, today, for which similar considerations apply as in the case of [ɪ]. (The symbol /ᵿ/ is sometimes used in these cases, similarly to /ᵻ/.) Some speakers may also have a rounded schwa, [ɵ], used in words like omission [ɵˈmɪʃən].

- [i], as in happy, coffee, in many dialects (others have [ɪ] in this position). The phonemic status of this [i] is not easy to establish. Contemporary accounts regard it as a symbol representing a close front vowel that is neither the vowel of KIT nor that of FLEECE; it occurs in contexts where the contrast between these vowels is neutralized. Strictly speaking, therefore, [i] is not a phoneme but an archiphoneme. See happy-tensing.

- [u], as in influence, to each. This is the back rounded counterpart to [i] described above; its phonemic status is treated in the same works as cited there.

Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables is a significant feature of English. Syllables of the types listed above often correspond to a syllable containing a different vowel ("full vowel") used in other forms of the same morpheme where that syllable is stressed. For example, the first o in photograph, being stressed, is pronounced with the GOAT vowel, but in photography, where it is unstressed, it is reduced to schwa. Also, certain common words (a, an, of, for, etc.) are pronounced with a schwa when they are unstressed, although they have different vowels when they are in a stressed position (see Weak and strong forms in English).

Some unstressed syllables, however, retain full (unreduced) vowels, i.e. vowels other than those listed above. Examples are the /æ/ in ambition and the /aɪ/ in finite. Some phonologists regard such syllables as not being fully unstressed (they may describe them as having tertiary stress); some dictionaries have marked such syllables as having secondary stress. However linguists such as Ladefoged and Bolinger regard this as a difference purely of vowel quality and not of stress, and thus argue that vowel reduction itself is phonemic in English. Examples of words where vowel reduction seems to be distinctive for some speakers include chickaree vs. chicory (the latter has the reduced vowel of HAPPY, whereas the former has the FLEECE vowel without reduction), and Pharaoh vs. farrow (both have the GOAT vowel, but in the latter word it may reduce to [ɵ]).

Transcription variants

The choice of which symbols to use for phonemic transcriptions may reveal theoretical assumptions or claims on the part of the transcriber. English "lax" and "tense" vowels are distinguished by a synergy of features, such as height, length, and contour (monophthong vs. diphthong); different traditions in the linguistic literature emphasize different features. For example, if the primary feature is thought to be vowel height, then the non-reduced vowels of General American English may be represented according to the table to the left and below. If, on the other hand, vowel length is considered to be the deciding factor, the symbols in the table to the below and center may be chosen (this convention has sometimes been used because the publisher did not have IPA fonts available, though that is seldom an issue any longer.) The rightmost table lists the corresponding lexical sets.

If vowel transition is taken to be paramount, then the chart may look like one of these:

(The transcriber at left assumes that there is no phonemic distinction between semivowels and approximants, so that /ej/ is equivalent to /eɪ̯/.)

Many linguists combine more than one of these features in their transcriptions, suggesting they consider the phonemic differences to be more complex than a single feature.

Lexical stress

Lexical stress is phonemic in English. For example, the noun increase and the verb increase are distinguished by the positioning of the stress on the first syllable in the former, and on the second syllable in the latter. (See initial-stress-derived noun.) Stressed syllables in English are louder than non-stressed syllables, as well as being longer and having a higher pitch.

In traditional approaches, in any English word consisting of more than one syllable, each syllable is ascribed one of three degrees of stress: primary, secondary or unstressed. Ordinarily, in each such word there will be exactly one syllable with primary stress, possibly one syllable having secondary stress, and the remainder unstressed. For example, the word amazing has primary stress on the second syllable, while the first and third syllables are unstressed, whereas the word organization has primary stress on the fourth syllable, secondary stress on the first, and the second, third and fifth unstressed. This is often shown in pronunciation keys using the IPA symbols for primary and secondary stress (which are ˈ and ËŒ respectively), placed before the syllables to which they apply. The two words just given may therefore be represented (in RP) as /əˈmeɪzɪŋ/ and /ËŒÉ"ËÉ¡É™naɪˈzeɪʃən/.

Some analysts identify an additional level of stress (tertiary stress). This is generally ascribed to syllables that are pronounced with less force than those with secondary stress, but nonetheless contain a "full" or "unreduced" vowel (vowels that are considered to be reduced are listed under Vowels in unstressed syllables above). Hence the third syllable of organization, if pronounced with /aɪ/ as shown above (rather than being reduced to /ɪ/ or /ə/), might be said to have tertiary stress. (The precise identification of secondary and tertiary stress differs between analyses; dictionaries do not generally show tertiary stress, although some have taken the approach of marking all syllables with unreduced vowels as having at least secondary stress.)

In some analyses, then, the concept of lexical stress may become conflated with that of vowel reduction. An approach which attempts to separate these two is provided by Peter Ladefoged, who states that it is possible to describe English with only one degree of stress, as long as unstressed syllables are phonemically distinguished for vowel reduction. In this approach, the distinction between primary and secondary stress is regarded as a phonetic or prosodic detail rather than a phonemic feature â€" primary stress is seen as an example of the predictable "tonic" stress that falls on the final stressed syllable of a prosodic unit. For more details of this analysis, see Stress and vowel reduction in English.

For stress as a prosodic feature (emphasis of particular words within utterances), see Prosodic stress below.

Phonotactics

Phonotactics is the study of the sequences of phonemes that occur in languages and the sound structures that they form. In this study it is usual to represent consonants in general with the letter C and vowels with the letter V, so that a syllable such as 'be' is described as having CV structure. The IPA symbol used to show a division between syllables is the dot [.]. Syllabification is the process of dividing continuous speech into discrete syllables, a process in which the position of a syllable division is not always easy to decide upon.

Most languages of the world syllabify CVCV and CVCCV sequences as /CV.CV/ and /CVC.CV/ or /CV.CCV/, with consonants preferentially acting as the onset of a syllable containing the following vowel. According to one view, English is unusual in this regard, in that stressed syllables attract following consonants, so that ˈCVCV and ˈCVCCV syllabify as /ˈCVC.V/ and /ˈCVCC.V/, as long as the consonant cluster CC is a possible syllable coda; in addition, /r/ preferentially syllabifies with the preceding vowel even when both syllables are unstressed, so that CVrV occurs as /CVr.V/. This is the analysis used in the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. However, this view is not widely accepted, as explained in the following section.

Syllable structure

The syllable structure in English is (C)3V(C)5, with a near maximal example being strengths (/strɛŋkθs/, although it can be pronounced /strɛŋθs/). From the phonetic point of view, the analysis of syllable structures is a complex task: because of widespread occurrences of articulatory overlap, English speakers rarely produce an audible release of individual consonants in consonant clusters. This coarticulation can lead to articulatory gestures that seem very much like deletions or complete assimilations. For example, hundred pounds may sound like [hÊŒndɹɪb pÊ°aÊŠndz] and 'jumped back' (in slow speech, [dÊ'ÊŒmptbæk]) may sound like [dÊ'ÊŒmpbæk], but X-ray and electropalatographic studies demonstrate that inaudible and possibly weakened contacts or lingual gestures may still be made. Thus the second /d/ in hundred pounds does not entirely assimilate to a labial place of articulation, rather the labial gesture co-occurs with the alveolar one; the "missing" [t] in 'jumped back' may still be articulated, though not heard.

Division into syllables is a difficult area, and different theories have been proposed. A widely accepted approach is the maximal onsets principle: this states that, subject to certain constraints, any consonants in between vowels should be assigned to the following syllable. Thus the word 'leaving' should be divided /ˈliË.vɪŋ/ rather than */ˈliËv.ɪŋ/, and 'hasty' is /ˈheɪ.sti/ rather than */ˈheɪs.ti/ or */ˈheɪst.i/. However, when such a division results in an onset cluster which is not allowed in English, the division must respect this. Thus if the word 'extra' were divided */ˈe.kstrÉ™/ the resulting onset of the second syllable would be /kstr/, a cluster which does not occur in English. The division /ˈek.strÉ™/ is therefore preferred. If assigning a consonant or consonants to the following syllable would result in the preceding syllable ending in an unreduced short vowel, this is avoided. Thus the word 'comma' should be divided /ˈkÉ'm.É™/ and not */ˈkÉ'.mÉ™/, even though the latter division gives the maximal onset to the following syllable, because English syllables do not end in /É'/.

In some cases, no solution is completely satisfactory: for example, in British English (RP) the word 'hurry' could be divided /ˈhÊŒ.ri/ or /ˈhÊŒr.i/, but the former would result in an analysis with a syllable-final /ÊŒ/ (which is held to be non-occurring) while the latter would result in a syllable final /r/ (which is said not to occur in this accent). Some phonologists have suggested a compromise analysis where the consonant in the middle belongs to both syllables, and is described as ambisyllabic. In this way, it is possible to suggest an analysis of 'hurry' which comprises the syllables /hÊŒr/ and /ri/, the medial /r/ being ambisyllabic. Where the division coincides with a word boundary, or the boundary between elements of a compound word, it is not usual in the case of dictionaries to insist on the maximal onsets principle in a way that divides words in a counter-intuitive way; thus the word 'hardware' would be divided /ˈhÉ'Ë.dweÉ™/ by the M.O.P., but dictionaries prefer the division /ˈhÉ'Ëd.weÉ™/.

In the approach used by the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, Wells claims that consonants syllabify with the preceding rather than following vowel when the preceding vowel is the nucleus of a more salient syllable, with stressed syllables being the most salient, reduced syllables the least, and full unstressed vowels ("secondary stress") intermediate. But there are lexical differences as well, frequently but not exclusively with compound words. For example, in dolphin and selfish, Wells argues that the stressed syllable ends in /lf/, but in shellfish, the /f/ belongs with the following syllable: /ˈdÉ'lf.ɪn/, /ˈself.ɪʃ/ â†' [ˈdÉ'É«fɨn], [ˈseÉ«fɨʃ], but /ˈʃel.fɪʃ/ â†' [ˈʃeÉ«Ë'fɪʃ], where the /l/ is a little longer and the /ɪ/ is not reduced. Similarly, in toe-strap Wells argues that the second /t/ is a full plosive, as usual in syllable onset, whereas in toast-rack the second /t/ is in many dialects reduced to the unreleased allophone it takes in syllable codas, or even elided: /ˈtoÊŠ.stræp/, /ˈtoÊŠst.ræk/ â†' [ˈtÊ°oË'ÊŠstɹæp], [ˈtÊ°oÊŠs(tÌš)ɹʷæk]; likewise nitrate /ˈnaɪ.treɪt/ â†' [ˈnʌɪtɹ̥ʷeɪt] with a voiceless /r/ (and for some people an affricated tr as in tree), vs night-rate /ˈnaɪt.reɪt/ â†' [ˈnʌɪt̚ɹʷeɪt] with a voiced /r/. Cues of syllable boundaries include aspiration of syllable onsets and (in the US) flapping of coda /t, d/ (a tease /É™.ˈtiËz/ â†' [əˈtÊ°iËz] vs. at ease /æt.ˈiËz/ â†' [æɾˈiËz]), epenthetic stops like [t] in syllable codas (fence /ˈfens/ â†' [ˈfents] but inside /ɪn.ˈsaɪd/ â†' [ɪnˈsaɪd]), and r-colored vowels when the /r/ is in the coda vs. labialization when it is in the onset (key-ring /ˈkiË.rɪŋ/ â†' [ˈkÊ°iËɹʷɪŋ] but fearing /ˈfiËr.ɪŋ/ â†' [ˈfɪəɹɪŋ]).

Onset

The following can occur as the onset:

Notes:

- For a number of speakers, /tr/ and /dr/ tend to affricate, so that tree resembles "chree", and dream resembles "jream". This is sometimes transcribed as [tʃr] and [dÊ'r] respectively, but the pronunciation varies and may, for example, be closer to [tÊ‚] and [dÊ] or with a fricative release similar in quality to the rhotic, i.e. [tɹÌ̊ɹ̥], [dɹÌɹ], or [tÊ‚É»], [dÊÉ»].

- In some dialects, especially Shetlandic English, /wr/ (rather than /r/) occurs in words beginning in wr- (write, wrong, wren, etc.).

- Words beginning in unusual consonant clusters that originated in Latinized Greek loanwords tend to drop the first phoneme, as in */bd/, */fθ/, */ɡn/, */hr/, */kn/, */ks/, */kt/, */kθ/, */mn/, */pn/, */ps/, */pt/, */tm/, and */θm/, which have become /d/ (bdellium), /θ/ (phthisis), /n/ (gnome), /r/ (rhythm), /n/ (cnidoblast), /z/ (xylophone), /t/ (ctenophore), /θ/ (chthonic), /n/ (mnemonic), /n/ (pneumonia), /s/ (psychology), /t/ (pterodactyl), /m/ (tmesis), and /m/ (asthma). However, the onsets /sf/, /sfr/, /skl/, /sθ/, and /θl/ have remained intact.

- The onset /hw/ is simplified to /w/ in many dialects (wineâ€"whine merger).

- There is an on-going sound change (yod-dropping) by which /j/ as the final consonant in a cluster is being lost. In RP, words with /sj/ and /lj/ can usually be pronounced with or without this sound, e.g. [suËt] or [sjuËt]. For some speakers of English, including some British speakers, the sound change is more advanced and so, for example, General American does not contain the onsets /tj/, /dj/, /nj/, /θj/, /sj/, /stj/, /zj/, or /lj/. Words that would otherwise begin in these onsets drop the /j/: e.g. tube (/tuËb/), during (/ˈdÊŠrɪŋ/), new (/nuË/), Thule (/ˈθuËliË/), suit (/suËt/), student (/ˈstuËdÉ™nt/), Zeus (/zuËs/), lurid (/ˈlÊŠrɪd/). In some dialects, such Welsh English, /j/ may occur in more combinations; for example in /tʃj/ (chew), /dÊ'j/ (Jew), /ʃj/ (sure), and /slj/ (slew).

- Many clusters beginning with /ʃ/ and paralleling native clusters beginning with /s/ are found initially in German and Yiddish loanwords, such as /ʃl/, /ʃp/, /ʃt/, /ʃm/, /ʃn/, /ʃpr/, /ʃtr/ (in words such as schlep, spiel, shtick, schmuck, schnapps, Shprintzen's, strudel). /ʃw/ is found initially in the Hebrew loanword schwa. Before /r/ however, the native cluster is /ʃr/. The opposite cluster /sr/ is found in loanwords such as Sri Lanka, but this can be nativized by changing it to /ʃr/.

- Other onsets

Certain English onsets appear only in contractions: e.g. /zbl/ ('sblood), and /zw/ or /dzw/ ('swounds or 'dswounds). Some, such as /pʃ/ (pshaw), /fw/ (fwoosh), or /vr/ (vroom), can occur in interjections. An archaic voiceless fricative plus nasal exists, /fn/ (fnese), as does an archaic /snj/ (snew).

A few other onsets occur in further (anglicized) loan words, including /bw/ (bwana), /mw/ (moiré), /nw/ (noire), /zw/ (zwieback), /kv/ (kvetch), /ʃv/ (schvartze), /tv/ (Tver), /vl/ (Vladimir), and /zl/ (zloty).

Some clusters of this type can be converted to regular English phonotactics by simplifying the cluster: e.g. /(d)z/ (dziggetai), /(h)r/ (Hrolf), /kr(w)/ (croissant), /(p)f/ (pfennig), /(f)θ/ (phthalic), and /(t)s/ (tsunami).

Others can be replaced by native clusters differing only in voice: /zb ~ sp/ (sbirro), and /zɡr ~ skr/ (sgraffito).

Nucleus

The following can occur as the nucleus:

- All vowel sounds

- /m/, /n/ and /l/ in certain situations (see below under word-level rules)

- /r/ in rhotic varieties of English (e.g. General American) in certain situations (see below under word-level rules)

Coda

Most (in theory, all) of the following except those that end with /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /Ê'/, /tʃ/ or /dÊ'/ can be extended with /s/ or /z/ representing the morpheme -s/-z. Similarly, most (in theory, all) the following except those that end with /t/ or /d/ can be extended with /t/ or /d/ representing the morpheme -t/-d.

Wells (1990) argues that a variety of syllable codas are possible in English, even /ntr, ndr/ in words like entry /ˈɛntr.ɪ/ and sundry /ˈsÊŒndr.ɪ/, with /tr, dr/ being treated as affricates along the lines of /tʃ, dÊ'/. He argues that the traditional assumption that pre-vocalic consonants form a syllable with the following vowel is due to the influence of languages like French and Latin, where syllable structure is CVC.CVC regardless of stress placement. Disregarding such contentious cases, which do not occur at the ends of words, the following sequences can occur as the coda:

Note: For some speakers, a fricative before /θ/ is elided so that these never appear phonetically: /fɪfθ/ becomes [fɪθ], /sɪksθ/ becomes [sɪkθ], /twɛlfθ/ becomes [twɛɫθ].

Syllable-level rules

- Both the onset and the coda are optional

- /j/ at the end of an onset cluster (/pj/, /bj/, /tj/, /dj/, /kj/, /fj/, /vj/, /θj/, /sj/, /zj/, /hj/, /mj/, /nj/, /lj/, /spj/, /stj/, /skj/) must be followed by /uË/ or /ÊŠÉ™/

- Long vowels and diphthongs are not found before /Å‹/ except for the mimetic words boing and oink

- /ʊ/ is rare in syllable-initial position (although, in the northern half of England, [ʊ] is used for /ʌ/ and is common at the start of syllables)

- Stop + /w/ before /uË, ÊŠ, ÊŒ, aÊŠ/ (all presently or historically /u(Ë)/) are excluded

- Sequences of /s/ + C1 + V̆ + C1, where C1 is a consonant other than /t/ and V̆ is a short vowel, are virtually nonexistent

- The distinction between "long" and "short" vowels is conflated before /Å‹/, the only vowels that occur before /Å‹/ in native words being /ɪ æ ÊŒ É'/ (as in sing sang sung song), plus /É› ÊŠ/ in assimilated non-native words such as ginseng and Sung (Dynasty), /É"ɪ/ in the mimetic words boing and oink, and /aÊŠ/ in a few proper names such as Taung.

Word-level rules

- /É™/ does not occur in stressed syllables

- /Ê'/ does not occur in word-initial position in native English words although it can occur syllable-initially, e.g. luxurious /lʌɡˈÊ'ÊŠÉ™riÉ™s/

- /m/, /n/, /l/ and, in rhotic varieties, /r/ can be the syllable nucleus (i.e. a syllabic consonant) in an unstressed syllable following another consonant, especially /t/, /d/, /s/ or /z/

- Certain short vowel sounds, called checked vowels, cannot occur without a coda in a single-syllable word. In RP, the following short vowel sounds are checked: /ɪ/, /É›/, /æ/, /É'/, /ÊŒ/, and /ÊŠ/.

Prosody

The prosodic features of English â€" stress, rhythm, and intonation â€" can be described as follows.

Prosodic stress

Prosodic stress is extra stress given to words or syllables when they appear in certain positions in an utterance, or when they receive special emphasis.

According to Ladefoged's analysis (as referred to under Lexical stress above), English normally has prosodic stress on the final stressed syllable in an intonation unit. This is said to be the origin of the distinction traditionally made at the lexical level between primary and secondary stress: when a word like admiration (traditionally transcribed as something like /ˌædmɨˈreɪʃən/) is spoken in isolation, or at the end of a sentence, the syllable ra (the final stressed syllable) is pronounced with greater force than the syllable ad, although when the word is not pronounced with this final intonation there may be no difference between the levels of stress of these two syllables.

Prosodic stress can shift for various pragmatic functions, such as focus or contrast. For instance, in the dialogue Is it brunch tomorrow? No, it's dinner tomorrow, the extra stress shifts from the last stressed syllable of the sentence, tomorrow, to the last stressed syllable of the emphasized word, dinner.

Grammatical function words are usually prosodically unstressed, although they can acquire stress when emphasized (as in Did you find the cat? Well, I found a cat). Many English function words have distinct strong and weak pronunciations; for example, the word a in the last example is pronounced /eɪ/, while the more common unstressed a is pronounced /ə/. See Weak and strong forms in English.

Rhythm

English is claimed to be a stress-timed language. That is, stressed syllables tend to appear with a more or less regular rhythm, while non-stressed syllables are shortened to accommodate this. For example, in the sentence 'One make of car is better than another', the syllables 'one', 'make', 'car', 'bett' and 'noth' will be stressed and relatively long, while the other syllables will be considerably shorter. The theory of stress-timing predicts that each of the three unstressed syllables in between 'bett' and 'noth' will be shorter than the syllable 'of' between 'make' and 'car' because three syllables must fit into the same amount of time as that available for 'of'. However, it should not be assumed that all varieties of English are stress-timed in this way. The English spoken in the West Indies, in Africa and in India are probably better characterized as syllable-timed, though the lack of an agreed scientific test for categorizing an accent or language as stress-timed or syllable-timed may lead one to doubt the value of such a characterization.

Intonation

Phonological contrasts in intonation can be said to be found in three different and independent domains. In the work of Halliday the following names are proposed:

- Tonality for the distribution of continuous speech into tone groups

- Tonicity for the placing of the principal accent on a particular syllable of a word, making it the tonic syllable. This is the domain also referred to as prosodic stress or sentence stress.

- Tone for the choice of pitch movement on the tonic syllable. (The use of the term "tone" in this sense should not be confused with the tone of tone languages, such as Chinese).

These terms ("the Three T's") have been used in more recent work, though they have been criticized for being difficult to remember. American systems such as ToBI also identify contrasts involving boundaries between intonation phrases (Halliday's "Tonicity"), placement of pitch accent ("Tonality") and choice of tone or tones associated with the pitch accent ("Tone").

Example of phonological contrast involving placement of intonation unit boundaries (boundary marked by |):

-

-

- a) Those who ran quickly | escaped. (the only people who escaped were those who ran quickly)

- b) Those who ran | quickly escaped. (the people who ran escaped quickly)

-

Example of phonological contrast involving placement of tonic syllable (marked by capital letters):

-

-

- a) I have plans to LEAVE. (= I am planning to leave)

- b) I have PLANS to leave. (= I have some drawings to leave)

-

Example of phonological contrast (British English) involving choice of tone (\ = falling tone, \/ = fall-rise tone)

-

-

- a) She didn't break the record because of the \ WIND. (= she did not break the record, because the wind held her up)

- b) She didn't break the record because of the \/ WIND. (= she did break the record, but not because of the wind)

-

It has been frequently claimed that there is a contrast involving tone between Wh-questions and yes/no questions, the former being said to have falling tone (e.g. "Where did you \PUT it?") and the latter a rising tone (e.g. "Are you going /OUT?"), though studies of spontaneous speech have shown frequent exceptions to this rule. "Tag questions" asking for information are said to carry rising tones (e.g. "They are coming on Tuesday, /AREN'T they?) while those asking for confirmation have falling tone (e.g. "Your name's John, \ISN'T it).

History of English pronunciation

English consonants have been remarkably stable over time, and have undergone few changes in the last 1500 years. On the other hand, English vowels have been quite unstable. Not surprisingly, then, the main differences between modern dialects almost always involve vowels.

Around the late 14th century, English began to undergo the Great Vowel Shift, in which

- The high long vowels [iË] and [uË] in words like price and mouth became diphthongized, first to [əɪ] and [əʊ] (where they remain today in some environments in some accents such as Canadian English) and later to their modern values [aɪ] and [aÊŠ]. This is not unique to English, as this also happened in Dutch (first shift only, but in dialects and other non-standard varieties frequently both) and German (both shifts).

- The other long vowels became higher:

- [eË] became [iË] (for example meet).

- [aË] became [eË] (later diphthongized to [eɪ], for example name).

- [oË] became [uË] (for example goose).

- [É"Ë] became [oË] (later diphthongized to [əʊ] (RP) and [oÊŠ] (GA), for example bone).

Later developments complicate the picture: whereas in Geoffrey Chaucer's time food, good, and blood all had the vowel [oË] and in William Shakespeare's time they all had the vowel [uË], in modern pronunciation good has shortened its vowel to [ÊŠ] and blood has shortened and lowered its vowel to [ÊŒ] in most accents. In Shakespeare's day (late 16th-early 17th century), many rhymes were possible that no longer hold today. For example, in his play The Taming of the Shrew, shrew rhymed with woe.

Dialectal differences

æ-tensing

æ-tensing is a phenomenon found in a good number of varieties of American English by which the vowel /æ/ has a longer, higher, and usually diphthongal pronunciation in some environments (especially before a nasal consonant in many American dialects), usually to something like [eə]. Some American accents, for example those of New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, make a marginal phonemic distinction between /æ/ and /eə/ although the two occur largely in mutually exclusive environments.

Badâ€"lad split

The badâ€"lad split refers to the situation in some varieties of southern British English and Australian English, where a long phoneme /æË/ in words like bad contrasts with a short /æ/ in words like lad.

Cotâ€"caught merger

The cotâ€"caught merger is a sound change by which the vowel of words like caught, talk, and tall (/É"Ë/), is pronounced the same as the vowel of words like cot, rock, and doll (/É'/ in New England (however, this is not to imply that all dialects of New England English have the cot-caught merger) /É'Ë/ elsewhere). This merger is very common in North American English, being found in approximately 40% of American speakers and virtually all Canadian speakers.

Fatherâ€"bother merger

The fatherâ€"bother merger is the pronunciation of the short O /É'/ in words such as "bother" identically to the broad A /É'Ë/ of words such as "father", is extremely common in the United States and Canada except in New England and the Maritime provinces; Because of the extreme commonness of this merger in many North American dialects, some American dictionaries use the same symbol for these vowels in their pronunciation guides.

See also

References

Bibliography

- Bacsfalvi, P. (2010), “Attaining the lingual components of /r/ with ultrasound for three adolescents with cochlear implantsâ€. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 34 (3): 206â€"217.

- Ball, M., Lowry, O., & McInnis, L. (2006), “Distributional and stylistic variation in /r/-misarticulations: A case studyâ€. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20: 2â€"3.

- Barry, M (1991), "Temporal Modelling of Gestures in Articulatory Assimilation", Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Aix-en-ProvenceÂ

- Barry, M (1992), "Palatalisation, Assimilation and Gestural Weakening in Connected Speech", Speech Communication, pp. vol.11, 393â€"400Â

- Browman, Catherine P.; Goldstein, Louis (1990), "Tiers in Articulatory Phonology, with Some Implications for Casual Speech", in Kingston, John C.; Beckman, Mary E., Papers in Laboratory Phonology I: Between the Grammar and Physics of Speech, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 341â€"376Â

- Brown, G. (1990), Listening to Spoken English, LongmanÂ

- Campbell, F., Gick, B., Wilson, I., Vatikiotis-Bateson, E. (2010), “Spatial and Temporal Properties of Gestures in North American English /r/â€. Child's Language and Speech, 53 (1): 49â€"69.

- Dalcher Villafaña, C., Knight, R.A., Jones, M.J., (2008), “Cue Switching in the Perception of Approximants: Evidence from Two English Dialectsâ€. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 14 (2): 63â€"64.

- Cercignani, Fausto (1975), "English Rhymes and Pronunciation in the Mid-Seventeenth Century", English Studies 56 (6): 513â€"518, doi:10.1080/00138387508597728Â

- Cercignani, Fausto (1981), Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford: Clarendon PressÂ

- Chomsky, Noam; Halle, Morris (1968), The Sound Pattern of English, New York: Harper & RowÂ

- Clements, G.N.; Keyser, S. (1983), CV Phonology: A Generative Theory of the Syllable, Cambridge, MA: MIT pressÂ

- Collins, B. and Mees, I. (2013), Practical Phonetics and Phonology, RoutledgeÂ

- Crystal, David (1969), Prosodic Systems and Intonation in English, Cambridge: Cambridge University PressÂ

- Espy-Wilson, C. (2004), “Articulatory Strategies, speech Acoustics and Variabilityâ€. From Sound to Sense June 11 â€" June 13 at MIT: 62â€"63

- Fudge, Erik C. (1984), English Word-stress, London: Allen and UnwinÂ

- Giegerich, H. (1992), English Phonology: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University PressÂ

- Gimson, A. C. (1962), An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English, London: Edward ArnoldÂ

- Gimson, A.C., ed. A.Cruttenden (2008), Pronunciation of English, HodderÂ

- Hagiwara, R., Fosnot, S. M., & Alessi, D. M. (2002). “Acoustic phonetics in a clinical setting: A case study of /r/-distortion therapy with surgical interventionâ€. Clinical linguistics & phonetics, 16 (6): 425â€"441.

- Halliday, M.A.K. (1967), Intonation and Grammar in British English, MoutonÂ

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1970), A Course in Spoken English: Intonation, London: Oxford University PressÂ

- Harris, John (1994), English Sound Structure, Oxford: BlackwellÂ

- Hoff, Erika, (2009), Language Development. Scarborough, Ontario. Cengage Learning, 2005.

- Howard, S. (2007), “The interplay between articulation and prosody in children with impaired speech: Observations from electropalatographic and perceptual analysisâ€. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9 (1): 20â€"35.

- Kingdon, Roger (1958), The Groundwork of English Intonation, London: LongmanÂ

- Kreidler, Charles (2004), The Pronunciation of English, BlackwellÂ

- Ladefoged, Peter (2001), A Course in Phonetics (4th (5th ed. 2006) ed.), Fort Worth: Harcourt College Publishers, ISBNÂ 0-15-507319-2Â

- Locke, John L., (1983), Phonological Acquisition and Change. New York, United States. Academic Press, 1983. Print.

- McCully, C. (2009), The Sound Structure of English, Cambridge: Cambridge University PressÂ

- McMahon, A. (2002), An Introduction to English Phonology, EdinburghÂ

- Nolan, Francis (1992), "The Descriptive Role of Segments: Evidence from Assimilation.", in Docherty, Gerard J.; Ladd, D. Robert, Papers in Laboratory Phonology II: Gesture, Segment, Prosody, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 261â€"280Â

- O'Connor, J. D.; Arnold, Gordon Frederick (1961), Intonation of Colloquial English, London: LongmanÂ

- Pike, Kenneth Lee (1945), The Intonation of American English, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan PressÂ

- Read, Charles (1986), Children's Creative Spelling, Routledge, ISBNÂ 0-7100-9802-2Â

- Roach, Peter (1982), "On the distinction between 'stress-timed' and 'syllable-timed' languages", in Crystal, David, Linguistic Controversies, ArnoldÂ

- Roach, Peter (2009), English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course, 4th Ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBNÂ 0-521-78613-4Â

- Roach, Peter (2004), "British English: Received Pronunciation", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 34 (2): 239â€"245, doi:10.1017/S0025100304001768Â

- Roca, Iggy; Johnson, Wyn (1999), A Course in Phonology, Blackwell PublishingÂ

- Selkirk, E. (1982), "The Syllable", in van der Hulst, H.; Smith, N., The Structure of Phonological Representations, Dordrecht: ForisÂ

- Sharf, D.J., Benson, P.J. (1982), “Identification of synthesized/r-w/continua for adult and child speakersâ€. Donald J. Acoustical Society of America, 71 (4):1008â€"1015.

- Tench, P. (1996), The Intonation Systems of English, CassellÂ

- Trager, George L.; Smith, Henry Lee (1951), An Outline of English Structure, Norman, OK: Battenburg PressÂ

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Cambridge University PressÂ

- Wells, John C. (1990), "Syllabification and allophony", in Ramsaran, Susan, Studies in the Pronunciation of English: A Commemorative Volume in Honour of A. C. Gimson, London: Routledge, pp. 76â€"86Â

- Wells, John (2006), English Intonation, Cambridge: Cambridge University PressÂ

- Wise, Claude Merton (1957), Applied Phonetics, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Zsiga, Elizabeth (2003), "Articulatory Timing in a Second Language: Evidence from Russian and English", Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 399â€"432, doi:10.1017/s0272263103000160Â

External links

- Animation of all sounds of English classified by manner, place and voice

- Seeing Speech Accent Map is a site with real articulatory recordings of English speakers, with a clickable IPA chart.

- Sounds of English (includes animations and descriptions)

- Howjsay Enter a word to hear it spoken. About 100,000 words in British English with alternative pronunciations.

- The sounds of English and the International Phonetic Alphabet (www.antimoon.com). Includes mp3 audio samples of all the English phonemes.

- The Chaos by Gerard Nolst Trenité. A poem first published in an appendix to the 4th edition of the Dutchman's schoolbook "Drop Your Foreign Accent: engelsche uitspraakoefeningen" (Haarlem: H D Tjeenk Willink & Zoon. The first version of the poem was entitled De Chaos, gave words with problematic spellings in italics, but had only 146 lines. Later versions contain about 800 of the worst irregularities in English spelling and pronunciation.

- Chris Upwood on The Classic Concordance of Cacographic Chaos

Posting Komentar